Favorites

General book blog.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 2106

Tolson, Melvin B.. A Gallery of Harlem Portraits. Columbia. 1979. University of Missouri Press. 0826202764. Edited and with an afterword by Robert M. Farnsworth. 276 pages. hardcover. Jacket art by Jerry Dadds.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

A Gallery of Harlem Portraits is Melvin B. Tolson's first book-length collection of poems. It was written in the 1930s when Tolson was immersed in the writings of the Harlem Renaissance, the subject of his master's thesis at Columbia University, and will provide scholars and critics a rich insight into how Tolson's literary picture of Harlem evolved. Modeled on Edgar Lee Master's Spoon River Anthology and showing the influence of Browning and Whitman, it is rooted in the Harlem Renaissance in its fascination with Harlem's cultural and ethnic diversity and its use of musical forms. Robert M. Farnsworth's afterword elucidates these and other literary influences. Tolson eventually attempted to incorporate the technical achievements of T.S. Eliot and the New Criticism into a complex modern poetry which would accurately represent the extraordinary tensions, paradoxes, and sophistication, both highbrow and lowbrow, of modern Harlem. As a consequence his position in literary history is problematical. The publication of this earliest of his manuscripts will help clarify Tolson's achievement and surprise many of his readers with its readily accessible, warmly human poetic portraiture.

MELVIN B. TOLSON (February 6, 1898 – August 29, 1966) was an American Modernist poet, educator, columnist, and politician. His work concentrated on the experience of African Americans and includes several long historical poems. His work was influenced by his study of the Harlem Renaissance, although he spent nearly all of his career in Texas and Oklahoma. Tolson is the protagonist of the 2007 biopic The Great Debaters. The film, produced by Oprah Winfrey, is based on his work with students at predominantly-black Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, and their debate with University of Southern California(USC). Tolson is portrayed by Denzel Washington, who also directed the film. Born in Moberly, Missouri, Tolson was one of four children of Reverend Alonzo Tolson, a Methodist minister, and Lera (Hurt) Tolson, a seamstress of African-Creek ancestry. Alonzo Tolson was also of mixed race, the son of an enslaved woman and her white master. He served at various churches in the Missouri and Iowa area until settling longer in Kansas City. Reverend Tolson studied throughout his life to add to the limited education he had first received, even taking Latin, Greek and Hebrew by correspondence courses. Both parents emphasized education for their children. Melvin Tolson graduated from Lincoln High School in Kansas City in 1919. He enrolled at Fisk University but transferred to Lincoln University, Pennsylvania the next year for financial reasons. Tolson graduated with honors in 1924. In 1922, Melvin Tolson married Ruth Southall of Charlottesville, Virginia, whom he had met as a student at Lincoln University. Their first child was Melvin Beaunorus Tolson, Jr., who, as an adult, became a professor at the University of Oklahoma. He was followed by Arthur Lincoln, who as an adult became a professor at Southern University; Wiley Wilson; and Ruth Marie Tolson. All children were born by 1928. In 1930-31 Tolson took a leave of absence from teaching to study for a Master's degree at Columbia University. His thesis project, "The Harlem Group of Negro Writers", was based on his extensive interviews with members of the Harlem Renaissance. His poetry was strongly influenced by his time in New York. He completed his work and was awarded the master's degree in 1940. After graduation, Tolson and his wife moved to Marshall, Texas, where he taught speech and English at Wiley College (1924–1947). The small, historically black Methodist Episcopal college had a high reputation among blacks in the South and Tolson became one of its stars. In addition to teaching English, Tolson used his high energies in several directions at Wiley. He built an award-winning debate team, the Wiley Forensic Society. During their tour in 1935, they broke through the color barrier and competed against the University of Southern California, which they defeated. There he also co-founded the black intercollegiate Southern Association of Dramatic and Speech Arts, and directed the theater club. In addition, he coached the junior varsity football team. Tolson mentored students such as James L. Farmer, Jr. and Heman Sweatt, who later became civil rights activists. He encouraged his students not only to be well-rounded people but also to stand up for their rights. This was a controversial position in the segregated U.S. South of the early and mid-20th century. In 1947 Tolson began teaching at Langston University, a historically black college in Langston, Oklahoma, where he worked for the next 17 years. He was a dramatist and director of the Dust Bowl Theater at the university. One of his students at Langston was Nathan Hare, the black studies pioneer who became the founding publisher of the journal The Black Scholar. In 1947 Liberia appointed Tolson its Poet Laureate. In 1953 he completed a major epic poem in honor of the nation's centennial, the Libretto for the Republic of Liberia. Tolson entered local politics and served three terms as mayor of Langston from 1954 to 1960. In 1947, Tolson was accused of having been active in organizing farm laborers and tenant farmers during the late 1930s (though the nature of his activities is unclear) and of having radical leftist associations. The film, The Great Debaters, portrays him as having been a possible Communist. In the film, Tolson's arrest for union organizing galvanizes the black community of the town of Marshall, Texas. Tolson was a man of impressive intellect who created poetry that was “funny, witty, humoristic, slapstick, rude, cruel, bitter, and hilarious,” as reviewer Karl Shapiro described the Harlem Gallery. In 1965, Tolson was appointed to a two-year term at Tuskegee Institute, where he was Avalon Poet. He died after cancer surgery in Dallas, Texas, on August 29, 1966. He was buried in Guthrie, Oklahoma. From 1930 on, Tolson began writing poetry. He also wrote two plays by 1937, although he did not continue to work in this genre. In 1941, he published his poem "Dark Symphony" in Atlantic Monthly. Some critics believe it is his greatest work, in which he compared and contrasted African-American and European-American history. In 1944 Tolson published his first poetry collection Rendezvous with America, which includes Dark Symphony. He was especially interested in historic events which had fallen into obscurity. In the late 1940s, after he left his teaching position at Wiley, The Washington Tribune hired Tolson to write a weekly column, which he called "Cabbage and Caviar". Tolson's Libretto for the Republic of Liberia (1953), another major work, is in the form of an epic poem in an eight-part, rhapsodic sequence. It is considered a major modernist work. Tolson's final work to appear in his lifetime, the long poem Harlem Gallery, was published in 1965. The poem consists of several sections, each beginning with a letter of the Greek alphabet. The poem concentrates on African-American life. It was a striking change from his first works, and was composed in a jazz style with quick changes and intellectually dense, rich allusions. In 1979 a collection of Tolson's poetry was published posthumously, entitled A Gallery of Harlem Portraits. These were poems written during his year in New York. They represented a mixture of various styles, including short narratives in free verse. This collection was influenced by the loose form of Edgar Lee Masters' Spoon River Anthology. An urban, racially diverse and culturally rich community is presented in A Gallery of Harlem Portraits. With increasing interest in Tolson and his literary period, in 1999 the University of Virginia published a collection of his poetry entitled Harlem Gallery and Other Poems of Melvin B. Tolson, edited by Raymond Nelson. Robert M. Farnsworth is Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and an author in the genres of biography and literary criticism. He has written about prominent literary figures and civil rights activists including Melvin Tolson and Leon Jordan. Farnsworth was born in 1929 in Detroit, Michigan. He graduated from the University of Michigan and earned a PhD from Tulane University in 1957. Farnsworth wrote a biography of assassinated civil rights leader Leon Jordan. Jordan had helped to found a political organization known as Freedom, Inc. before his long-unsolved murder. Farnsworth had met Jordan in 1961 and said he was "in awe of him." He also wrote a biography of poet Melvin B. Tolson titled Melvin B. Tolson, 1898-1966: Plain and Poetic Prophecy. The book was reviewed in World Literature Today. In Rhetoric at the Margins: Revising the History of Writing Instruction in American Colleges, 1873-1947, author David Gold wrote, "Robert M. Farnsworth's finely balanced and carefully researched biography does little worse than suggest that Tolson's love for argumentation may have intimidated his children, who nonetheless respected him and loved him dearly." Farnsworth also edited Caviar and Cabbage: Selected Columns by Melvin B. Tolson from the Washington Tribune, 1937-1944. The book included selections from a weekly newspaper column on black culture that Tolson had written for seven years. He authored a biography of journalist Edgar Snow titled From Vagabond to Journalist: Edgar Snow in Asia, 1928--1941. The work was described in Kirkus Reviews as a "resonant briefing on an American who bore eloquent witness to a turning point in Asian history." The book was one of two Snow biographies published in 1996. Farnsworth is an emeritus professor of English at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

MELVIN B. TOLSON (February 6, 1898 – August 29, 1966) was an American Modernist poet, educator, columnist, and politician. His work concentrated on the experience of African Americans and includes several long historical poems. His work was influenced by his study of the Harlem Renaissance, although he spent nearly all of his career in Texas and Oklahoma. Tolson is the protagonist of the 2007 biopic The Great Debaters. The film, produced by Oprah Winfrey, is based on his work with students at predominantly-black Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, and their debate with University of Southern California(USC). Tolson is portrayed by Denzel Washington, who also directed the film. Born in Moberly, Missouri, Tolson was one of four children of Reverend Alonzo Tolson, a Methodist minister, and Lera (Hurt) Tolson, a seamstress of African-Creek ancestry. Alonzo Tolson was also of mixed race, the son of an enslaved woman and her white master. He served at various churches in the Missouri and Iowa area until settling longer in Kansas City. Reverend Tolson studied throughout his life to add to the limited education he had first received, even taking Latin, Greek and Hebrew by correspondence courses. Both parents emphasized education for their children. Melvin Tolson graduated from Lincoln High School in Kansas City in 1919. He enrolled at Fisk University but transferred to Lincoln University, Pennsylvania the next year for financial reasons. Tolson graduated with honors in 1924. In 1922, Melvin Tolson married Ruth Southall of Charlottesville, Virginia, whom he had met as a student at Lincoln University. Their first child was Melvin Beaunorus Tolson, Jr., who, as an adult, became a professor at the University of Oklahoma. He was followed by Arthur Lincoln, who as an adult became a professor at Southern University; Wiley Wilson; and Ruth Marie Tolson. All children were born by 1928. In 1930-31 Tolson took a leave of absence from teaching to study for a Master's degree at Columbia University. His thesis project, "The Harlem Group of Negro Writers", was based on his extensive interviews with members of the Harlem Renaissance. His poetry was strongly influenced by his time in New York. He completed his work and was awarded the master's degree in 1940. After graduation, Tolson and his wife moved to Marshall, Texas, where he taught speech and English at Wiley College (1924–1947). The small, historically black Methodist Episcopal college had a high reputation among blacks in the South and Tolson became one of its stars. In addition to teaching English, Tolson used his high energies in several directions at Wiley. He built an award-winning debate team, the Wiley Forensic Society. During their tour in 1935, they broke through the color barrier and competed against the University of Southern California, which they defeated. There he also co-founded the black intercollegiate Southern Association of Dramatic and Speech Arts, and directed the theater club. In addition, he coached the junior varsity football team. Tolson mentored students such as James L. Farmer, Jr. and Heman Sweatt, who later became civil rights activists. He encouraged his students not only to be well-rounded people but also to stand up for their rights. This was a controversial position in the segregated U.S. South of the early and mid-20th century. In 1947 Tolson began teaching at Langston University, a historically black college in Langston, Oklahoma, where he worked for the next 17 years. He was a dramatist and director of the Dust Bowl Theater at the university. One of his students at Langston was Nathan Hare, the black studies pioneer who became the founding publisher of the journal The Black Scholar. In 1947 Liberia appointed Tolson its Poet Laureate. In 1953 he completed a major epic poem in honor of the nation's centennial, the Libretto for the Republic of Liberia. Tolson entered local politics and served three terms as mayor of Langston from 1954 to 1960. In 1947, Tolson was accused of having been active in organizing farm laborers and tenant farmers during the late 1930s (though the nature of his activities is unclear) and of having radical leftist associations. The film, The Great Debaters, portrays him as having been a possible Communist. In the film, Tolson's arrest for union organizing galvanizes the black community of the town of Marshall, Texas. Tolson was a man of impressive intellect who created poetry that was “funny, witty, humoristic, slapstick, rude, cruel, bitter, and hilarious,” as reviewer Karl Shapiro described the Harlem Gallery. In 1965, Tolson was appointed to a two-year term at Tuskegee Institute, where he was Avalon Poet. He died after cancer surgery in Dallas, Texas, on August 29, 1966. He was buried in Guthrie, Oklahoma. From 1930 on, Tolson began writing poetry. He also wrote two plays by 1937, although he did not continue to work in this genre. In 1941, he published his poem "Dark Symphony" in Atlantic Monthly. Some critics believe it is his greatest work, in which he compared and contrasted African-American and European-American history. In 1944 Tolson published his first poetry collection Rendezvous with America, which includes Dark Symphony. He was especially interested in historic events which had fallen into obscurity. In the late 1940s, after he left his teaching position at Wiley, The Washington Tribune hired Tolson to write a weekly column, which he called "Cabbage and Caviar". Tolson's Libretto for the Republic of Liberia (1953), another major work, is in the form of an epic poem in an eight-part, rhapsodic sequence. It is considered a major modernist work. Tolson's final work to appear in his lifetime, the long poem Harlem Gallery, was published in 1965. The poem consists of several sections, each beginning with a letter of the Greek alphabet. The poem concentrates on African-American life. It was a striking change from his first works, and was composed in a jazz style with quick changes and intellectually dense, rich allusions. In 1979 a collection of Tolson's poetry was published posthumously, entitled A Gallery of Harlem Portraits. These were poems written during his year in New York. They represented a mixture of various styles, including short narratives in free verse. This collection was influenced by the loose form of Edgar Lee Masters' Spoon River Anthology. An urban, racially diverse and culturally rich community is presented in A Gallery of Harlem Portraits. With increasing interest in Tolson and his literary period, in 1999 the University of Virginia published a collection of his poetry entitled Harlem Gallery and Other Poems of Melvin B. Tolson, edited by Raymond Nelson. Robert M. Farnsworth is Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and an author in the genres of biography and literary criticism. He has written about prominent literary figures and civil rights activists including Melvin Tolson and Leon Jordan. Farnsworth was born in 1929 in Detroit, Michigan. He graduated from the University of Michigan and earned a PhD from Tulane University in 1957. Farnsworth wrote a biography of assassinated civil rights leader Leon Jordan. Jordan had helped to found a political organization known as Freedom, Inc. before his long-unsolved murder. Farnsworth had met Jordan in 1961 and said he was "in awe of him." He also wrote a biography of poet Melvin B. Tolson titled Melvin B. Tolson, 1898-1966: Plain and Poetic Prophecy. The book was reviewed in World Literature Today. In Rhetoric at the Margins: Revising the History of Writing Instruction in American Colleges, 1873-1947, author David Gold wrote, "Robert M. Farnsworth's finely balanced and carefully researched biography does little worse than suggest that Tolson's love for argumentation may have intimidated his children, who nonetheless respected him and loved him dearly." Farnsworth also edited Caviar and Cabbage: Selected Columns by Melvin B. Tolson from the Washington Tribune, 1937-1944. The book included selections from a weekly newspaper column on black culture that Tolson had written for seven years. He authored a biography of journalist Edgar Snow titled From Vagabond to Journalist: Edgar Snow in Asia, 1928--1941. The work was described in Kirkus Reviews as a "resonant briefing on an American who bore eloquent witness to a turning point in Asian history." The book was one of two Snow biographies published in 1996. Farnsworth is an emeritus professor of English at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 1823

Sebald, W. G.. Vertigo. New York. 2000. New Directions. 0811214303. Translated from the German by Michael Hulse. 263 pages. hardcover. Cover by Semadar Megged.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

Vertigo is the third novel New Directions has published by W.G. Sebald, one of themost enormously acclaimed European writers of our time. Vertigo, W.G. Sebald’s first novel, never before translated into English, is perhaps his most amazing and certainly his most alarming. Sebald—the acknowledged master of memory’s uncanniness—takes the painful pleasures of unknowability to new intensities in Vertigo. Here in their first flowering are the signature elements of Sebald’s hugely acclaimed novels The Emigrants and The Rings of Saturn. An unnamed narrator, beset by nervous ailments, is again our guide on a hair-raising journey through the past and across Europe, amid restless literary ghosts—Kafka, Stendhal, Casanova. In four dizzying sections, the narrator plunges the reader into vertigo, into that ‘swimming of the head,’ as Webster’s defines it: in other words, into that state so unsettling, so fascinating, and so ‘stunning and strange,’ as The New York Times Book Review declared about The Emigrants, that it is ‘like a dream you want to last forever.’

W. G. SEBALD was born in Wertach im Allgau, Germany, in 1944. He studied German language and literature in Freiburg, Switzerland, and Manchester. He taught at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, for thirty years, becoming professor of European literature in 1987, and from 1989 to 1994 he was the first director of the British Centre for Literary Translation. His previously translated books - THE RINGS OF SATURN, THE EMIGRANTS, VERTIGO, and AUSTERLITZ - have won a number of international awards, including the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Award, the Berlin Literature Prize, and the Literatur Nord Prize. He died in December 2001.

W. G. SEBALD was born in Wertach im Allgau, Germany, in 1944. He studied German language and literature in Freiburg, Switzerland, and Manchester. He taught at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, for thirty years, becoming professor of European literature in 1987, and from 1989 to 1994 he was the first director of the British Centre for Literary Translation. His previously translated books - THE RINGS OF SATURN, THE EMIGRANTS, VERTIGO, and AUSTERLITZ - have won a number of international awards, including the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Award, the Berlin Literature Prize, and the Literatur Nord Prize. He died in December 2001.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 1734

School of the Sun by Ana Maria Matute. New York. 1963. Pantheon Books. Translated from the Spanish by Elaine Kerrigan. 242 pages.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

A Spanish writer’s approach by the intimist route to the still unassuaged griefs of the Civil War. What happens is that the protected bourgeois world in which it is possible to go on with the pretext of childishness at fourteen is split open by the realities of war, or, rather, the realities of which the war is the expression.

Ana María Matute Ana María Matute Ausejo (26 July 1925 – 25 June 2014) was the most prominent woman writer of 20th century Spain. Her novels and short stories have won many prestigious literary awards including the Premio Nacional de Literatura, Premio Nadal, Premio de la Crítica and Premio Café de Gijón. She was the third woman to receive the Cervantes Prize for her literary oeuvre. She is considered to be one of the foremost novelists of the posguerra, the period immediately following the Spanish Civil War. She studied at the international school of Hilversum in the Netherlands. She has been a guest lecturer to the universities of Oklahoma, Indiana and Virginia. Matute was born on 26 July 1925. At the age of four she almost died from a chronic kidney infection, and was taken to live with her grandparents in Mansilla de la Sierra, a small town in the mountains, for a period of recovery. Matute says that she was profoundly influenced by the villagers whom she met during her time there. This influence can be seen in such works as those published in the 1961 anthology Historias de la Artamila (‘Stories about the Artamila’, all of which deal with the people that Matute met during her recovery). Settings reminiscent of that town are also often used as settings for her other work. Matute was ten years old when the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, and this conflict is said to have had the greatest impact on Matute's writing. She considered not only ‘the battles between the two factions, but also the internal aggression within each one’. The war resulted in Francisco Franco's rise to power, starting in 1936 and escalating until 1939, when he took control of the entire country. Franco established a dictatorship which lasted thirty-six years, until his death in 1975. The violence brought on by the war continued through much of his reign. Since Matute matured as a writer in this posguerra period under Franco's oppressive regime, some of the most recurrent themes in her works are violence, alienation, misery, and especially the loss of innocence. Her work was sometimes censored by the Franco regime, and at least once she was fined because of her writings. She published her first story, ‘The Boy Next Door,’ when she was only 17 years old. Matute was known for her sympathetic treatment of the lives of children and adolescents, their feelings of betrayal and isolation, and their rites of passage. She often interjected such elements as myth, fairy tale, the supernatural, and fantasy into her works. Matute was a university professor. She traveled to various countries, especially the United States, as a lecturer. She was outspoken about subjects such as the benefits of emotional suffering, the constant changing of a human being, and how innocence is never completely lost. She was an honorary member of the Hispanic Society of America and a member of the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese. She won the Spanish literary award, the Premio Nadal, in 1958 for the first novel of the trilogy, ‘Los Mercaderes’. On 25 June 2014, Matute died of a heart attack at the age of 88.

Ana María Matute Ana María Matute Ausejo (26 July 1925 – 25 June 2014) was the most prominent woman writer of 20th century Spain. Her novels and short stories have won many prestigious literary awards including the Premio Nacional de Literatura, Premio Nadal, Premio de la Crítica and Premio Café de Gijón. She was the third woman to receive the Cervantes Prize for her literary oeuvre. She is considered to be one of the foremost novelists of the posguerra, the period immediately following the Spanish Civil War. She studied at the international school of Hilversum in the Netherlands. She has been a guest lecturer to the universities of Oklahoma, Indiana and Virginia. Matute was born on 26 July 1925. At the age of four she almost died from a chronic kidney infection, and was taken to live with her grandparents in Mansilla de la Sierra, a small town in the mountains, for a period of recovery. Matute says that she was profoundly influenced by the villagers whom she met during her time there. This influence can be seen in such works as those published in the 1961 anthology Historias de la Artamila (‘Stories about the Artamila’, all of which deal with the people that Matute met during her recovery). Settings reminiscent of that town are also often used as settings for her other work. Matute was ten years old when the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, and this conflict is said to have had the greatest impact on Matute's writing. She considered not only ‘the battles between the two factions, but also the internal aggression within each one’. The war resulted in Francisco Franco's rise to power, starting in 1936 and escalating until 1939, when he took control of the entire country. Franco established a dictatorship which lasted thirty-six years, until his death in 1975. The violence brought on by the war continued through much of his reign. Since Matute matured as a writer in this posguerra period under Franco's oppressive regime, some of the most recurrent themes in her works are violence, alienation, misery, and especially the loss of innocence. Her work was sometimes censored by the Franco regime, and at least once she was fined because of her writings. She published her first story, ‘The Boy Next Door,’ when she was only 17 years old. Matute was known for her sympathetic treatment of the lives of children and adolescents, their feelings of betrayal and isolation, and their rites of passage. She often interjected such elements as myth, fairy tale, the supernatural, and fantasy into her works. Matute was a university professor. She traveled to various countries, especially the United States, as a lecturer. She was outspoken about subjects such as the benefits of emotional suffering, the constant changing of a human being, and how innocence is never completely lost. She was an honorary member of the Hispanic Society of America and a member of the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese. She won the Spanish literary award, the Premio Nadal, in 1958 for the first novel of the trilogy, ‘Los Mercaderes’. On 25 June 2014, Matute died of a heart attack at the age of 88.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 1609

God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything by Christopher Hitchens. New York/Boston. 2007. Twelve. 307 pages. hardcover. 9780446579803. Jacket design by Anne Twomey.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

From the author hailed as ‘one of the A most brilliant journalists of our time’ (London Observer) comes a book that redefines the debate about religion in public life. With his unique brand of erudition and wit, Christopher Hitchens addresses the most urgent issue of our time: the malignant force of religion in the world. In this eloquent argument with the faithful, Hitchens makes the ultimate case against religion (and for a more secular approach to life) through a close and learned reading of the major religious texts. Hitchens tells the personal story of his own dangerous encounters with religion and describes his intellectual journey toward a secular view of life based on science and reason, in which the heavens are replaced by the Hubble telescope’s awesome view of the universe, and Moses and the burning bush give way to the beauty and symmetry of the double helix. ‘God did not make us,’ he writes. ‘We made God.’ Religion, he explains, is a distortion of our origins, our nature, and the cosmos. We damage our children - and endanger our world - by indoctrinating them. Whether lifelong believer, devout atheist, or someone who remains uncertain about the role of religion in our lives, you will want to consider and engage in the arguments within these pages.

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS was educated at Balliol College, Oxford, and. is a columnist for The Nation, Washington editor for Harper’s, and a book reviewer for Newsday. Christopher Hitchens joined Vanity Fair as a contributing editor in November 1992 and wrote regularly for the magazine until 2011. In May 2011, he won the National Magazine Award for Columns and Commentary for a series of columns on his having cancer. In recent years, Hitchens was a contributing editor to The Atlantic, where he wrote a monthly essay on books, and a regular columnist at Slate. From 1982 to 2002, he wrote a biweekly column for The Nation. Throughout his singular career Christopher Hitchens wrote for The New Statesman, the London Evening Standard, London’s Daily Express, Harper’s, The Spectator, and The Times Literary Supplement, among others. His books include THE TRIAL OF HENRY KISSINGER (VERSO, 2001), LETTERS TO A YOUNG CONTRARIAN (BASIC, 2001), GOD IS NOT GREAT: HOW RELIGION POISONS EVERYTHING (TWELVE, 2007), HITCH-22: A MEMOIR (TWELVE, 2010), and ARGUABLY: ESSAYS BY CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS (Twelve, 2011), a collection of his later essays. Christopher Hitchens died on December 15, 2011.

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS was educated at Balliol College, Oxford, and. is a columnist for The Nation, Washington editor for Harper’s, and a book reviewer for Newsday. Christopher Hitchens joined Vanity Fair as a contributing editor in November 1992 and wrote regularly for the magazine until 2011. In May 2011, he won the National Magazine Award for Columns and Commentary for a series of columns on his having cancer. In recent years, Hitchens was a contributing editor to The Atlantic, where he wrote a monthly essay on books, and a regular columnist at Slate. From 1982 to 2002, he wrote a biweekly column for The Nation. Throughout his singular career Christopher Hitchens wrote for The New Statesman, the London Evening Standard, London’s Daily Express, Harper’s, The Spectator, and The Times Literary Supplement, among others. His books include THE TRIAL OF HENRY KISSINGER (VERSO, 2001), LETTERS TO A YOUNG CONTRARIAN (BASIC, 2001), GOD IS NOT GREAT: HOW RELIGION POISONS EVERYTHING (TWELVE, 2007), HITCH-22: A MEMOIR (TWELVE, 2010), and ARGUABLY: ESSAYS BY CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS (Twelve, 2011), a collection of his later essays. Christopher Hitchens died on December 15, 2011.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 1537

The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector. Manchester. 1986. Carcanet. Translated From The Portuguese By Giovanni Pontiero. 96 pages. Cover: Michael Helme. 0856356263.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

Clarice Lispector said that THE HOUR OF THE STAR was made without Words. a mute photograph. a silence. a question. ’ Macabea comes to Rio from the backwoods of Brazil, poor in all but illusion. The story of her brief life is told by Rodriqo S. M. , a cosmopolitan character, remote from her except in one respect: he is looking for an identity. In telling her story he recoils time after time: the hypnotic tension of THE HOUR OF THE STAR, Clarice Lispector’s masterpiece, is in his pained relationship with Macabea. Macabea finds a room in the slums. A bad typist, a virgin, her favourite drink is Coca-Cola. Incompetent and inexperienced, she loves Hollywood films and looks hungrily in the mirror for proof that she, too. has a future. She is a foil for her bullying employer, her philandering boy-friend, and her workmate Gloria, who has all the attributes of body and spirit which Macabea lacks. Macabea doesn’t go to pieces: she is simply emptied by her experience, ignorance and isolation. Yet she believes that glamour and a square meal await her somewhere: she is credulous, too, so that a fortune-teller, mistelling her future, provides her with a brief, ecstatic moment of transformation. The narrator peels back the prejudices of one class, one sex, about another, until in the end he stands naked before the mortality of the character he has created.

glamour and a square meal await her somewhere: she is credulous, too, so that a fortune-teller, mistelling her future, provides her with a brief, ecstatic moment of transformation. The narrator peels back the prejudices of one class, one sex, about another, until in the end he stands naked before the mortality of the character he has created.

CLARICE LISPECTOR, one of the most significant writers in twentieth-century Brazilian literature, died in 1977. Her works range from literary essays to novelistic fiction and children’s literature. Lispector is best known in Latin America and Europe; only recently have some of her works been translated from Portuguese into English. Other English translations include FAMILY TIES, THE APPLE IN THE DARK and THE HOUR OF THE STAR.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 1669

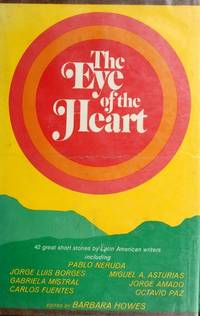

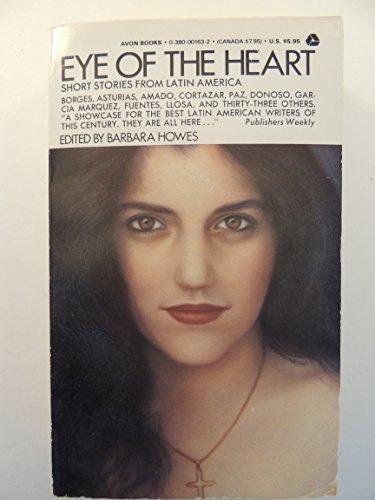

Howes, Barbara (editor). Eye of the Heart: Short Stories From Latin America. Indianapolis. 1973. Bobbs-Merrill. 0672516373. 415 pages. hardcover.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

Here in a single volume are forty-two short stories from the finest writers in Latin American literature. The contributors include not only highly respected names (Neruda, Borges, Cortazar, Mistral, Fuentes, Asturias, Amado, Paz) but also the most controversial and experimental storytellers, some of whom have emerged only in the last few years (Donoso, de Assis, Novas-Calvo, Bosch, Reyes, and dozens more). The Minneapolis Tribune describes THE EYE OF THE HEART as ‘a substantial sampling . . . gifts of truth. Their authors saw with the heart.’ And Jorge Luis Borges calls this book ‘quite impressive. All of the important writers are there and the stories are all good . . . I know nothing like it now.’

more). The Minneapolis Tribune describes THE EYE OF THE HEART as ‘a substantial sampling . . . gifts of truth. Their authors saw with the heart.’ And Jorge Luis Borges calls this book ‘quite impressive. All of the important writers are there and the stories are all good . . . I know nothing like it now.’

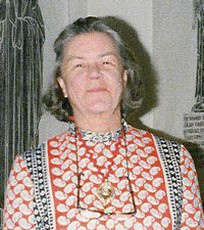

Barbara Howes (May 1, 1914 New York City - February 24, 1996 Bennington, Vermont) was an American poet. She was adopted by well-to-do Massachusetts family, and reared chiefly in Chestnut Hill, where she attended Beaver Country Day School. She graduated from Bennington College in 1937. She worked briefly for the Southern Tenant Farmers Union in Mississippi, and then edited the literary magazine, Chimera, from 1943 to 1947 and lived in Greenwich Village. In 1947 she married the poet William Jay Smith, and they lived for a time in England and Italy. They had two sons, David Smith, and Gregory. They divorced in the mid-1960s, and she lived in Pownal, Vermont. In 1971, she signed a letter protesting proposed cuts to the School of the Arts, Columbia University. Her work was published in, Atlantic, Chicago Review, New Directions, New Republic, New Yorker, New York Times Book Review, Saturday Review, Southern Review, University of Kansas Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and Yale Review.

Barbara Howes (May 1, 1914 New York City - February 24, 1996 Bennington, Vermont) was an American poet. She was adopted by well-to-do Massachusetts family, and reared chiefly in Chestnut Hill, where she attended Beaver Country Day School. She graduated from Bennington College in 1937. She worked briefly for the Southern Tenant Farmers Union in Mississippi, and then edited the literary magazine, Chimera, from 1943 to 1947 and lived in Greenwich Village. In 1947 she married the poet William Jay Smith, and they lived for a time in England and Italy. They had two sons, David Smith, and Gregory. They divorced in the mid-1960s, and she lived in Pownal, Vermont. In 1971, she signed a letter protesting proposed cuts to the School of the Arts, Columbia University. Her work was published in, Atlantic, Chicago Review, New Directions, New Republic, New Yorker, New York Times Book Review, Saturday Review, Southern Review, University of Kansas Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and Yale Review.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 2120

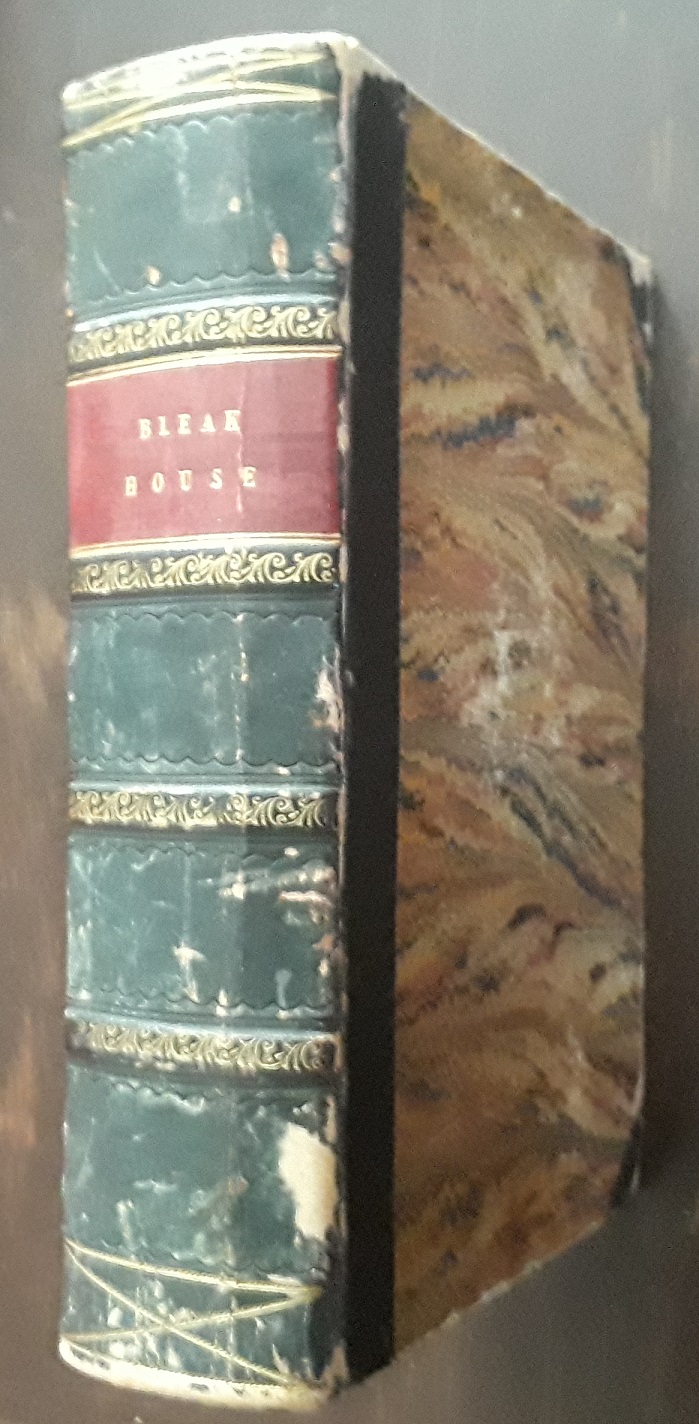

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. London. 1853. Bradbury and Evans. Illustrations by H. K. Browne. 39 etched plates. 624 pages. hardcover.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

BLEAK HOUSE opens in a London shrouded by an all - pervading fog - a fog that swirls about the Court of Chancery, where the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce lies lost in endless litigation. This drawn - out lawsuit over an inheritance stands at the center of a scathing portrayal of a moribund legal system and of a society permeated with greed, deception, delusion, and guilt. In no other work are the many facets of Dickens' genius - his powers of characterization, dramatic construction, social satire, and poetic evocation - so memorably combined. Peopled by an immense gallery of vivid characters, major and minor, comic and tragic, in settings which range from the mansion of a fear - haunted noblewoman to the squalor of the London slums, this superb example of narrative art has been ranked by Edmund Wilson as 'The masterpiece of [Dickens'] middle period.' Geoffrey Tillotson writes: 'BLEAK HOUSE.. .is, all told, the finest literary work the nineteenth century produced in England. . . . Dickens was the supreme literary genius of his time.

Charles John Huffam Dickens (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's most memorable fictional characters and is generally regarded as the greatest novelist of the Victorian period. During his life, his works enjoyed unprecedented fame, and by the twentieth century his literary genius was broadly acknowledged by critics and scholars. His novels and short stories continue to be widely popular.

Charles John Huffam Dickens (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's most memorable fictional characters and is generally regarded as the greatest novelist of the Victorian period. During his life, his works enjoyed unprecedented fame, and by the twentieth century his literary genius was broadly acknowledged by critics and scholars. His novels and short stories continue to be widely popular.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 2028

The Greek Way by Edith Hamilton. New York. 1930. Norton. 247 pages.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

'Five hundred years before Christ in a little town on the far western border of the settled and civilized world, a strange new power was at work. Athens had entered upon her brief and magnificent flowering of genius which so molded the world of mind and of spirit that our mind and spirit today are different. What was then produced of art and of thought has never been surpasses and very rarely equaled, and the stamp of it is upon all the art and all the thought of the Western world.' A perennial favorite in many different editions, Edith Hamilton's best-selling THE GREEK WAY captures the spirit and achievements of Greece in the fifth century B. C. A retired headmistress when she began her writing career in the 1930s, Hamilton immediately demonstrated a remarkable ability to bring the world of ancient Greece to life, introducing that world to the twentieth century. The New York Times called THE GREEK WAY a 'book of both cultural and critical importance.'

'book of both cultural and critical importance.'

Edith Hamilton won the National Achievement Award in 1950, received honorary degrees of Doctor of Letters from Yale University, the University of Rochester, and the University of Pennsylvania, and was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1957 she was many an honorary citizen of Athens and was decorated with the Golden Cross of the Order of Benefaction by King Paul of Greece.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 2252

Men God Forgot by Albert Cossery. Berkeley. 1946. Circle Editions. Translated From French By H. E. 139 pages.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

Not that the little people are to be found exclusively in the little nations such as Egypt. Quite the contrary. For the moment, however, it is not the little people so much in whom we are interested as the forgotten people of the world. They exist everywhere, mostly in the big nations, and often in the biggest cities. They are lodged in the heart of civilization, like a cancer. They are the people you seldom notice when you go for a walk, or when the innumerable street lamps begin to blaze. As Cossery says, 'that is how civilization makes itself felt, as lights which it scatters around it to blind the people.' - HENRY MILLER.

Albert Cossery (3 November 1913 – 22 June 2008) was an Egyptian-born French writer of Greek Orthodox Syro-Lebanese descent, born in Cairo. Albert Cossery was born to a well-off Levantine-Egyptian family in Cairo, where his parents were wealthy small-property owners. In 1998, he told Abdallah Naaman: ‘We are the ‘Shawams’ (Syro-Lebanese, referring to the Bilad al-Sham) of Egypt. My father is a Greek Orthodox native of the village of al-Qusayr, near Homs, in Syria. Upon arriving in Cairo at the end of the 19th century, our surname's pronunciation was simplified to ‘Cossery’ (from ‘Qusayri’).’ At the age of 17, inspired by reading Honoré de Balzac, emigrated to Paris. He came there to continue his studies which he never did to devote himself to, writing and settled permanently in the French capital in 1945, where he lived until his death in 2008. In 60 years he only wrote eight novels, in accordance with his philosophy of life in which ‘laziness’ is not a vice but a form of contemplation and meditation. In his own words: ‘So much beauty in the world, so few eyes to see it.’ At the age of 27 he published his first book, Les hommes oubliés de Dieu (‘Men God Forgot’). During his literary career he became close friend of other writers and artists such as Lawrence Durrell, Albert Camus, Jean Genet and Giacometti. Cossery died on 22 June 2008, aged 94. His books, which always take place in Egypt or other Arab countries, portray the contrast between poverty and wealth, the powerful and the powerless, in a witty although dramatic way. His writing mocks vanity and the narrowness of materialism and his principal characters are mainly vagrants, thieves or dandies that subvert the order of an unfair society. Often auto-biographical characters, like Teymour, the hero of the novel Un complot de saltimbanques, a young man that forges a diploma of chemical engineer after a life of enjoyment and lust abroad instead of study and gets back to his home town and enters in an unexpected intringue against the authorities with his dandy friends. He is considered by some to be the last genuine ‘anarchist’ or free thinking writer of western culture by his humorous and provocative although lucid and profound view of human relations and society. His writing style does not submit to an academic or experimental approach which makes him a vivid, catchy storyteller, without the boredom nor artificial ambiguity of some classical (which he is) or avantgarde writers. The sageness of his works are monuments to the freedom of being and thought against materialism, the contemporary obsession with consumption and productivity, the arrogance and abuse of authority, the vanity of social formalities and the injustice of the wealthy towards the poor. In 1990 Cossery was awarded the Grand Prix de La Francophonie de l´Académie française and in 2005 the Grand Prix Poncetton de la SGDL. The first of his books translated in English are Men God Forgot (first translated by Harold Edwards of Faruk University, Alexandria, Egypt, not by Henry Miller, whose note on Cossery appeared on a later 1963 City Lights Books edition, and published in the USA in 1946 by George Leite's Circle Editions of Berkeley), The House of Certain Death (New Directions, 1949), The Lazy Ones (New Directions, 1952), and Proud Beggars (Black Sparrow Press, 1981). Three more of Cossery's novels have since been published in English translation: Anna Moschovakis' The Jokers (NYRB Classics) and Alyson Waters' A Splendid Conspiracy and The Colors of Infamy (New Directions). As of 2012, Une ambition dans le désert and Les Fainéants dans la vallée fertile remain untranslated into English.

Albert Cossery (3 November 1913 – 22 June 2008) was an Egyptian-born French writer of Greek Orthodox Syro-Lebanese descent, born in Cairo. Albert Cossery was born to a well-off Levantine-Egyptian family in Cairo, where his parents were wealthy small-property owners. In 1998, he told Abdallah Naaman: ‘We are the ‘Shawams’ (Syro-Lebanese, referring to the Bilad al-Sham) of Egypt. My father is a Greek Orthodox native of the village of al-Qusayr, near Homs, in Syria. Upon arriving in Cairo at the end of the 19th century, our surname's pronunciation was simplified to ‘Cossery’ (from ‘Qusayri’).’ At the age of 17, inspired by reading Honoré de Balzac, emigrated to Paris. He came there to continue his studies which he never did to devote himself to, writing and settled permanently in the French capital in 1945, where he lived until his death in 2008. In 60 years he only wrote eight novels, in accordance with his philosophy of life in which ‘laziness’ is not a vice but a form of contemplation and meditation. In his own words: ‘So much beauty in the world, so few eyes to see it.’ At the age of 27 he published his first book, Les hommes oubliés de Dieu (‘Men God Forgot’). During his literary career he became close friend of other writers and artists such as Lawrence Durrell, Albert Camus, Jean Genet and Giacometti. Cossery died on 22 June 2008, aged 94. His books, which always take place in Egypt or other Arab countries, portray the contrast between poverty and wealth, the powerful and the powerless, in a witty although dramatic way. His writing mocks vanity and the narrowness of materialism and his principal characters are mainly vagrants, thieves or dandies that subvert the order of an unfair society. Often auto-biographical characters, like Teymour, the hero of the novel Un complot de saltimbanques, a young man that forges a diploma of chemical engineer after a life of enjoyment and lust abroad instead of study and gets back to his home town and enters in an unexpected intringue against the authorities with his dandy friends. He is considered by some to be the last genuine ‘anarchist’ or free thinking writer of western culture by his humorous and provocative although lucid and profound view of human relations and society. His writing style does not submit to an academic or experimental approach which makes him a vivid, catchy storyteller, without the boredom nor artificial ambiguity of some classical (which he is) or avantgarde writers. The sageness of his works are monuments to the freedom of being and thought against materialism, the contemporary obsession with consumption and productivity, the arrogance and abuse of authority, the vanity of social formalities and the injustice of the wealthy towards the poor. In 1990 Cossery was awarded the Grand Prix de La Francophonie de l´Académie française and in 2005 the Grand Prix Poncetton de la SGDL. The first of his books translated in English are Men God Forgot (first translated by Harold Edwards of Faruk University, Alexandria, Egypt, not by Henry Miller, whose note on Cossery appeared on a later 1963 City Lights Books edition, and published in the USA in 1946 by George Leite's Circle Editions of Berkeley), The House of Certain Death (New Directions, 1949), The Lazy Ones (New Directions, 1952), and Proud Beggars (Black Sparrow Press, 1981). Three more of Cossery's novels have since been published in English translation: Anna Moschovakis' The Jokers (NYRB Classics) and Alyson Waters' A Splendid Conspiracy and The Colors of Infamy (New Directions). As of 2012, Une ambition dans le désert and Les Fainéants dans la vallée fertile remain untranslated into English.

- Details

- Category: Favorites

- Hits: 2016

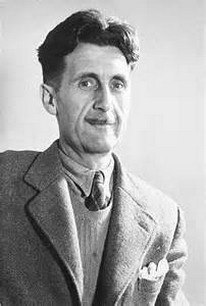

Dickens, Dali & Others by George Orwell. New York. 1946. Reynal & Hitchcock. 243 pages. hardcover.

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

FROM THE PUBLISHER -

Ten celebrated essays by a man universally regarded as a master of the essay form. Included are such classics as ‘Charles Dickens’, ‘The Art of Donald McGill’, ‘Boys’ Weeklies’, ‘Raffles and Miss Blandish’, and ‘Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali.’ This collection of essays by one of the most perceptive of contemporary English critics has the impact of a single unifying idea. Mr. Orwell’s studies in popular culture deal with writers, painters, prophets, illustrators and social commentators. With the exception of W. B. Yeats and Arthur Koestler, the people of whom he writes have all reached a large section of the public. In some cases their influence on popular consciousness has been enormous. The most extended of the essays is devoted to Charles Dickens. The fact that he has been equally claimed by liberals, radicals, and conservatives is the subject of this study in misunderstanding. The treatment of H. G. Wells is particularly timely in tis indication of the factors responsible for Wells’ recent defection from his lifelong belief in scientific progress as a cure-all for the world’s ills. Salvador Dali is subjected to a more merciless dissection than is usual in the case of this exponent of chi-chi and surrealism. There are spirited defenses of certain aspects of the life and work of two currently unpopular writers, Kipling and P. G. Wodehouse. In the interests of the truly popular culture which is generally ignored by critics of Mr. Orwell’s caliber there are three brilliant and fascinating essays dealing with boys’ magazines, picture postcards, and detective stories.

Eric Arthur Blair was born on 25 June 1903 to British parents in Motihari, Bengal Presidency, British India. There, Blair’s father, Richard Walmesley Blair, worked for the Opium Department of the Civil Service. His mother, Ida Mabel Blair (born Limouzin), brought him to England at the age of one. He did not see his father again until 1907, when Richard visited England for three  months before leaving again. Eric had an older sister named Marjorie, and a younger sister named Avril. He would later describe his family’s background as ‘lower-upper-middle class’. At the age of six, Blair was sent to a small Anglican parish school in Henley-on-Thames, which his sister had attended before him. He never wrote of his recollections of it, but he must have impressed the teachers very favourably, for two years later, he was recommended to the headmaster of one of the most successful preparatory schools in England at the time: St Cyprian’s School, in Eastbourne, Sussex. Blair attended St Cyprian’s by a private financial arrangement that allowed his parents to pay only half of the usual fees. At the school, he formed a lifelong friendship with Cyril Connolly, future editor of the magazine Horizon, in which many of his most famous essays were originally published. Many years later, Blair would recall his time at St Cyprian’s with biting resentment in the essay ‘Such, Such Were the Joys’. However, in his time at St. Cyprian’s, the young Blair successfully earned scholarships to both Wellington and Eton. After one term at Wellington, Blair moved to Eton, where he was a King’s Scholar from 1917 to 1921. Aldous Huxley was his French teacher for one term early in his time at Eton. Later in life he wrote that he had been ‘relatively happy’ at Eton, which allowed its students considerable independence, but also that he ceased doing serious work after arriving there. Reports of his academic performance at Eton vary; some assert that he was a poor student, while others claim the contrary. He was clearly disliked by some of his teachers, who resented what they perceived as disrespect for their authority. After Blair finished his studies at Eton, his family could not pay for university and his father felt that he had no prospect of winning a scholarship, so in 1922 he joined the Indian Imperial Police, serving at Katha and Moulmein in Burma. He came to hate imperialism, and when he returned to England on leave in 1927 he decided to resign and become a writer. He later used his Burmese experiences for the novel Burmese Days (1934) and in such essays as ‘A Hanging’ (1931) and ‘Shooting an Elephant’ (1936). Back in England he wrote to Ruth Pitter, a family acquaintance, and she and a friend found him a room in London, on the Portobello Road (a blue plaque is now on the outside of this house), where he started to write. It was from here that he sallied out one evening to Limehouse Causeway - following in the footsteps of Jack London - and spent his first night in a common lodging house, probably George Levy’s ‘kip’. For a while he ‘went native’ in his own country, dressing like other tramps and making no concessions, and recording his experiences of low life in his first published essay, ‘The Spike’, and the latter half of Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). In the spring of 1928, he moved to Paris, where his Aunt Nellie lived and died, hoping to make a living as a freelance writer. In the autumn of 1929, his lack of success reduced Blair to taking menial jobs as a dishwasher for a few weeks, principally in a fashionable hotel (the Hotel X) on the rue de Rivoli, which he later described in his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London, although there is no indication that he had the book in mind at the time. Ill and penniless, he moved back to England in 1929, using his parents’ house in Southwold, Suffolk, as a base. Writing what became Burmese Days, he made frequent forays into tramping as part of what had by now become a book project on the life of the poorest people in society. Meanwhile, he became a regular contributor to John Middleton Murry’s New Adelphi magazine. Blair completed Down and Out in 1932, and it was published early the next year while he was working briefly as a schoolteacher at a private school called Frays College near Hayes, Middlesex. He took the job as an escape from dire poverty and it was during this period that he managed to obtain a literary agent called Leonard Moore. Blair also adopted the pen name George Orwell just before Down and Out was published. In a November 15 letter to Leonard Moore, his agent, he left the choice of a pseudonym to Moore and to Victor Gollancz, the publisher. Four days later, Blair wrote Moore and suggested P. S. Burton, a name he used ‘when tramping,’ adding three other possibilities: Kenneth Miles, George Orwell, and H. Lewis Allways. Orwell drew on his work as a teacher and on his life in Southwold for the novel A Clergyman’s Daughter (1935), which he wrote at his parents’ house in 1934 after ill-health - and the urgings of his parents - forced him to give up teaching. From late 1934 to early 1936 he worked part-time as an assistant in a second-hand bookshop, Booklover’s Corner, in Hampstead. Having led a lonely and very solitary existence, he wanted to enjoy the company of other young writers, and Hampstead was a place for intellectuals, as well as having many houses with cheap bedsitters. He worked his experiences into the novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936). In early 1936, Orwell was commissioned by Victor Gollancz of the Left Book Club to write an account of poverty among the working class in the depressed areas of northern England, which appeared in 1937 as The Road to Wigan Pier. He was taken into many houses, simply saying that he wanted to see how people lived. He made systematic notes on housing conditions and wages and spent several days in the local public library consulting reports on public health and conditions in the mines. He did his homework as a social investigator. The first half of the book is a social documentary of his investigative touring in Lancashire and Yorkshire, beginning with an evocative description of work in the coal mines. The second half of the book, a long essay in which Orwell recounts his personal upbringing and development of political conscience, includes a very strong denunciation of what he saw as irresponsible elements of the left. Gollancz feared that the second half would offend Left Book Club readers, and inserted a mollifying preface to the book while Orwell was in Spain. Soon after completing his research for the book, Orwell married Eileen O’Shaughnessy. In December 1936, Orwell travelled to Spain primarily to fight, not to write, for the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War against Francisco Franco’s Fascist uprising. In a conversation with Philip Mairet, the editor of the New English Weekly, Orwell said: ‘This fascism. somebody’s got to stop it.’ To Orwell, liberty and democracy went together and, among other things, guaranteed the freedom of the artist; the present capitalist civilization was corrupt, but fascism would be morally calamitous. John McNair (1887-1968) is also quoted as saying in a conversation with Orwell: ‘He then said that this (writing a book) was quite secondary and his main reason for coming was to fight against Fascism.’ He went alone, and his wife joined him later. He joined the Independent Labour Party contingent, a group of some twenty-five Britons who joined the militia of the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM - Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista), a revolutionary Spanish communist political party with which the ILP was allied. The POUM, along with the radical wing of the anarcho-syndicalist CNT (the dominant force on the left in Catalonia), believed that Franco could be defeated only if the working class in the Republic overthrew capitalism - a position fundamentally at odds with that of the Spanish Communist Party and its allies, which (backed by Soviet arms and aid) argued for a coalition with bourgeois parties to defeat the Nationalists. In the months after July 1936 there was a profound social revolution in Catalonia, Aragon and other areas where the CNT was particularly strong. Orwell sympathetically describes the egalitarian spirit of revolutionary Barcelona when he arrived in Homage to Catalonia. According to his own account, Orwell joined the POUM rather than the Communist-run International Brigades by chance - but his experiences, in particular his and his wife’s narrow escape from the Communist purges in Barcelona in June 1937, greatly increased his sympathy for POUM and made him a life-long anti-Stalinist and a firm believer in what he termed Democratic Socialism, that is to say, in socialism combined with free debate and free elections. During his military service, Orwell was shot through the neck and nearly killed. At first it was feared that his voice would be permanently reduced to nothing more than a painful whisper. This wasn’t so, although the injury did affect his voice, giving it what was described as, ‘a strange, compelling quietness.’ He wrote in Homage to Catalonia that people frequently told him he was lucky to survive, but that he personally thought ‘it would be even luckier not to be hit at all.’ The Orwells then spent six months in Morocco in order to recover from his wound, and during this period, he wrote his last pre-World War II novel, Coming Up For Air. As the most English of all his novels, the alarms of war mingle with idyllic images of a Thames-side Edwardian childhood enjoyed by its protagonist, George Bowling. Much of the novel is pessimistic; industrialism and capitalism have killed the best of old England. There were also massive new external threats and George Bowling puts the totalitarian hypothesis of Borkenau, Orwell, Silone and Koestler in homely terms: ‘Old Hitler’s something different. So’s Joe Stalin. They aren’t like these chaps in the old days who crucified people and chopped their heads off and so forth, just for the fun of it. They’re something quite new - something that’s never been heard of before.’ After the ordeals of Spain and writing the book about it, most of Orwell’s formative experiences were over. His finest writing, his best essays and his great fame lay ahead. In 1940, Orwell closed up his house in Wallington and he and Eileen moved into 18 Dorset Chambers, Chagford Street, in the genteel neighbourhood of Marylebone, very close to Regent’s Park in central London. He supported himself by writing freelance reviews, mainly for the New English Weekly but also for Time and Tide and the New Statesman. He joined the Home Guard soon after the war began (and was later awarded the ‘British Campaign Medals/Defence Medal’). In 1941 Orwell took a job at the BBC Eastern Service, supervising broadcasts to India aimed at stimulating Indian interest in the war effort, at a time when the Japanese army was at India’s doorstep. He was well aware that he was engaged in propaganda, and wrote that he felt like ‘an orange that’s been trodden on by a very dirty boot’. The wartime Ministry of Information, which was based at Senate House, University of London, was the inspiration for the Ministry of Truth in Nineteen Eighty-Four. Nonetheless, Orwell devoted a good deal of effort to his BBC work, which gave him an opportunity to work closely with people like T. S. Eliot, E. M. Forster, Mulk Raj Anand and William Empson. Orwell’s decision to resign from the BBC followed a report confirming his fears about the broadcasts: very few Indians were listening. He wanted to become a war correspondent and also seems to have been impatient to begin work on Animal Farm. Despite the good salary, he resigned in September 1943 and in November became the literary editor of Tribune, the left-wing weekly then edited by Aneurin Bevan and Jon Kimche (it was Kimche who had been Box to Orwell’s Cox when they both worked as half-time assistants in the Hampstead bookshop in 1934-35). Orwell was on the staff until early 1945, contributing a regular column titled ‘As I Please.’ Anthony Powell and Malcolm Muggeridge had returned from overseas to finish the war in London. All three took to lunching regularly, usually at the Bodega just off the Strand or the Bourgogne in Soho, sometimes joined by Julian Symons (who seemed at the time to be Orwell’s true disciple), and David Astor, editor/owner of The Observer. In 1944, Orwell finished his anti-Stalinist allegory Animal Farm, which was first published in Britain on 17 August 1945 and in the U.S.A on the 26 August 1946 with great critical and popular success. Frank Morley, an editor Harcourt Brace, had come to Britain as soon as he could at the end of the War to see what readers were currently interested in. He asked to serve a week or so in Bowes and Bowes, a Cambridge bookshop. On his first day there customers kept asking for a book that had sold out - the second impression of Animal Farm. He left the counter, read the single copy left in the postal order department, went to London and bought the American rights. The royalties from Animal Farm were to provide Orwell with a comfortable income for the first time in his adult life. While Animal Farm was at the printer, and with the end of the War in sight, Orwell felt his old desire growing to be somehow in the thick of the action. David Astor asked him to act as a war correspondent for the Observer to cover the liberation of France and the early occupation of Germany, so Orwell left Tribune to do so. He was a close friend of Astor (some say the model for the wealthy publisher in Keep the Aspidistra Flying), and his ideas had a strong influence on Astor’s editorial policies. Astor, who died in 2001, is buried in the grave next to Orwell. Orwell and his wife adopted a baby boy, Richard Horatio Blair, born in May 1944. Orwell was taken ill again in Cologne in spring 1945. While he was sick there, his wife died during an operation in Newcastle to remove a tumour. She had not told him about this operation due to concerns about the cost and the fact that she thought she would make a speedy recovery. For the next four years Orwell mixed journalistic work - mainly for Tribune, the Observer and the Manchester Evening News, though he also contributed to many small-circulation political and literary magazines - with writing his best-known work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was published in 1949. Originally, Orwell was undecided between titling the book The Last Man in Europe and Nineteen Eighty-Four but his publisher, Fredric Warburg, helped him choose. The title was not the year Orwell had initially intended. He first set his story in 1980, but, as the time taken to write the book dragged on (partly because of his illness), that was changed to 1982 and, later, to 1984. He wrote much of the novel while living at Barnhill, a remote farmhouse on the island of Jura, which lies in the Gulf stream off the west coast of Scotland. It was an abandoned farmhouse with outbuildings near to the northern end of the island, lying at the end of a five-mile (8 km) heavily rutted track from Ardlussa, where the laird or landowner, Margaret Fletcher, lived and where the paved road, the only road on the island, came to an end. In 1948, he co-edited a collection entitled British Pamphleteers with Reginald Reynolds. In 1949, Orwell was approached by a friend, Celia Kirwan, who had just started working for a Foreign Office unit, the Information Research Department, which the Labour government had set up to publish anti-communist propaganda. He gave her a list of 37 writers and artists he considered to be unsuitable as IRD authors because of their pro-communist leanings. The list, not published until 2003, consists mainly of journalists (among them the editor of the New Statesman, Kingsley Martin) but also includes the actors Michael Redgrave and Charlie Chaplin. Orwell’s motives for handing over the list are unclear, but the most likely explanation is the simplest: that he was helping a friend in a cause - anti-Stalinism - that they both supported. There is no indication that Orwell abandoned the democratic socialism that he consistently promoted in his later writings - or that he believed the writers he named should be suppressed. Orwell’s list was also accurate: the people on it had all made pro-Soviet or pro-communist public pronouncements. In fact, one of the people on the list, Peter Smollett, the head of the Soviet section in the Ministry of Information, was later (after the opening of KGB archives) proven to be a Soviet agent, recruited by Kim Philby, and ‘almost certainly the person on whose advice the publisher Jonathan Cape turned down Animal Farm as an unhealthily anti-Soviet text’, although Orwell was unaware of this. In October 1949, shortly before his death, he married Sonia Brownell. Orwell died in London at the age of 46 from tuberculosis. He was in and out of hospitals for the last three years of his life. Having requested burial in accordance with the Anglican rite, he was interred in All Saints’ Churchyard, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire with the simple epitaph: ‘Here lies Eric Arthur Blair, born June 25, 1903, died January 21, 1950’; no mention is made on the gravestone of his more famous pen-name. He had wanted to be buried in the graveyard of the closest church to wherever he happened to die, but the graveyards in central London had no space. Fearing that he might have to be cremated, against his wishes, his widow appealed to his friends to see if any of them knew of a church with space in its graveyard. Orwell’s friend David Astor lived in Sutton Courtenay and negotiated with the vicar for Orwell to be buried there, although he had no connection with the village. Orwell’s son, Richard Blair, was raised by an aunt after his father’s death. He maintains a low public profile, though he has occasionally given interviews about the few memories he has of his father. Blair worked for many years as an agricultural agent for the British government.